The first African American man to become a licensed architect in the State of Texas was John Saunders Chase (1925-2012). His journey to this achievement was not a smooth one as in 1954 he had to petition the State for special permission to take the licensing exam. He passed the exam in the same year and started his own firm soon thereafter (because no Houston firms would hire him).

In college, Chase was one of the first African American architecture students to be admitted in 1950 to the University of Texas at Austin and was the first to graduate in 1952. An interesting clip of John S. Chase talking about the experience can be found on TheHistoryMakers.org.

In addition, Chase achieved many notable accomplishments in his career. In 1971, he was a founding member, and eventually chair and president of NOMA (National Organization of Minority Architects). He was also the first African American architect in Texas elected to become a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1977, among many other honors.

A Brief Synopsis

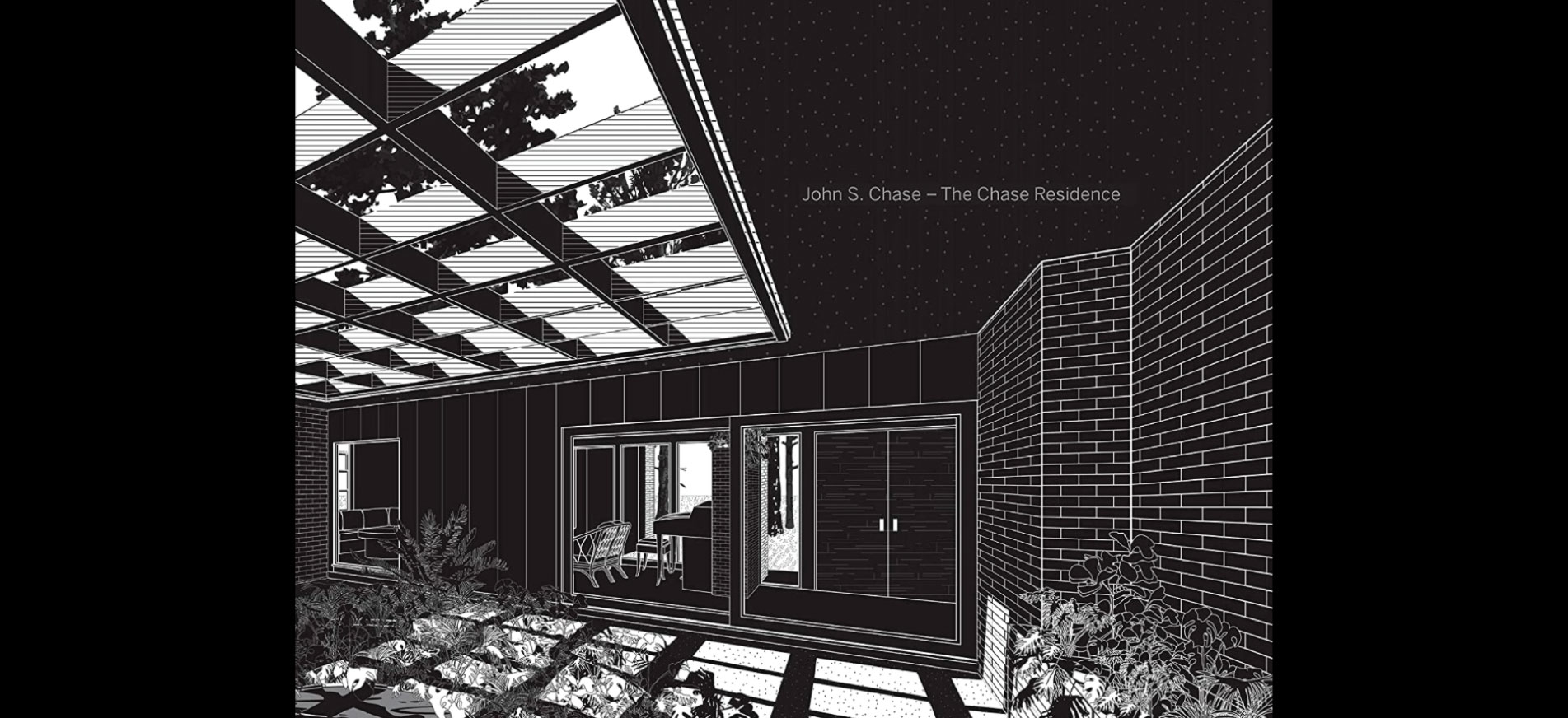

In a book released in 2020 entitled “John S. Chase—The Chase Residence” (the University of Texas Press), authors David Heymann, FAIA and Stephen Fox give us a glimpse into the life and work of this great architect. He was a figure in Texas history that paved the way for many others like him in the future.

The first half of the book, by David Heymann, takes the opportunity to invite us into an intimate glimpse of the evolution of his residence, designed by Chase himself, on Oakdale Circle in Houston Texas. The second half of the book, by Stephen Fox, discusses other notable structures that Chase designed in his career as an architect.

John S. Chase - The Chase Residence by David Heymann

Stage 1 - 1959

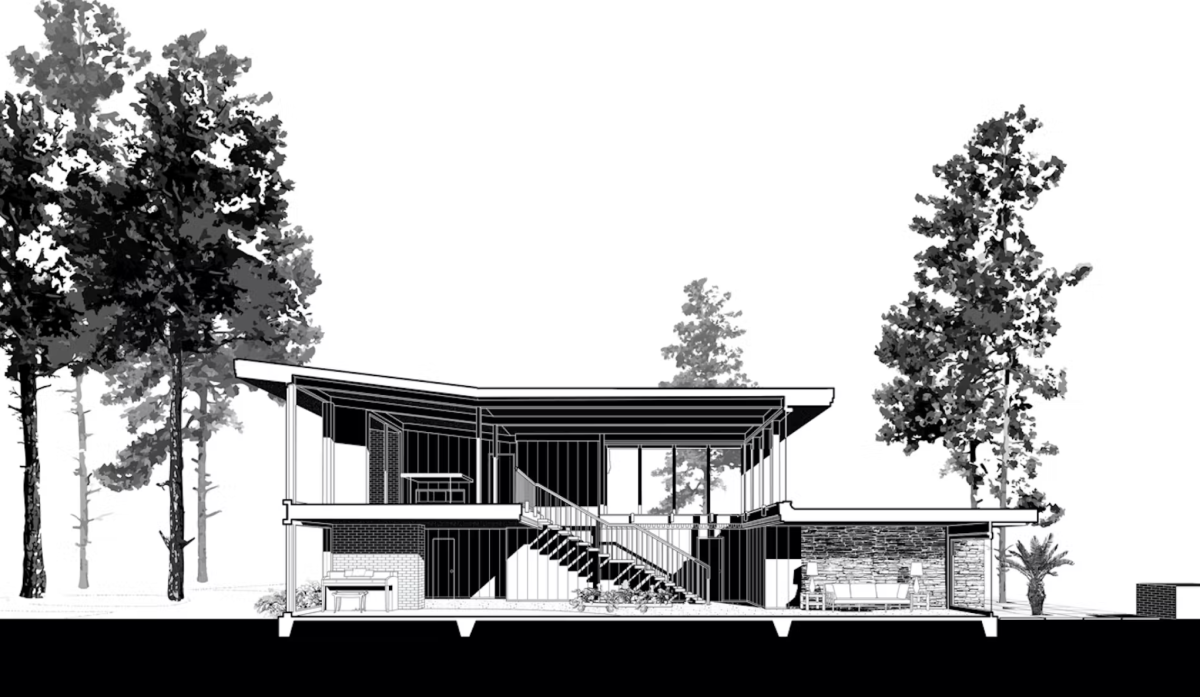

The Chase Residence was completed in 1959 after he and his wife, Drucie, had two sons. One feature of the home that was rare for the time period included a central courtyard open to the sky in the middle of the floor plan. Drucie didn’t know how she was going to utilize this for entertaining, but it proved to be one of the favorite features of the house for both residents and guests alike.

One of Chase’s design inspirations was American Architect, Frank Lloyd Wright. German-born modernist architect, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, was a design hero for Chase as well, giving the house’s occupants many opportunities for daylighting with expanses of glass providing views to the beautiful surrounding pine trees.

Chase soon took the opportunity to entertain in his home (thankfully his wife, Drucie, enjoyed entertaining as well) with a guest list that included their circle of friends, politicians, community leaders, and clergymen. One of the author’s favorite stories was about the bar that was cleverly designed to be concealed when certain guests were over. The Chases were Baptists and weren’t supposed to consume alcohol, so a sliding bookcase could be recessed into a pocket in the wall for evenings that included more lively entertaining, then rolled closed when more conservative guests were over.

Stage 2 - 1968

A third child, daughter Saundria, was born in the mid-1960s. This eventually caused Chase to redesign the home for his growing family with an expansion that included an upstairs addition.

The author points out that the architecture took a stylistic turn stating, “Chase added square wooden shingle trim blocks in a repetitive pattern onto the originally minimal fascia boards that run along all the roof edges… This geometric decoration also used indoors, subtly shifted the style from the elegant elitism of Mies to the confident populism of Wright.”

The author does an excellent job describing the architectural details that are in a likeness to the work of Chase’s architectural heroes, making it easy to visualize.

In a closing statement, the author makes an especially astute observation about the Chase Family,

“I think this is a central truth about the space. Here is the home of happy people, intent on succeeding as normal human beings in and despite an unfair world in which the possibility of that happiness and normalcy is and has been frequently if not constantly challenged.”

The Architecture of John S. Chase by Stephen Fox

In this section of the book, Fox discusses Chase's accomplishments, who his predecessors and contemporaries were in architecture, and the types of projects on which he worked. Fox states,

“Racial segregation meant that John Chase’s practice in the 1950s and 1960s had the same small-town, community focus of other mid-century, architectural sole practitioners in Texas. He designed a wide array of building types for African American professionals, business entrepreneurs, religious institutions, and labor unions.”

Later in Chase’s career, he would move on to bigger projects such as banks, government, and universities, with the largest collection of his buildings on the campus of Texas Southern University. Then in the 1970s, the architect began to utilize pre-cast concrete as a material and adopted a more “Brutalist” style of architecture (as many architects did in the 1970s).

Chase passed away in 2012 due to illness at the age of 87. His legacy lives on as a vital part of Texas architecture history.

The Verdict

The authors give a fascinating glimpse into the life and work of this trailblazing figure, John S. Chase, and how he helped to shape the landscape of civil rights in Texas through the practice of architecture. The imagery of both old photographs, sepia-toned floor plans, and 3D renderings was a great juxtaposition that contributed well to their storytelling.

The only thing that left us curious was the neighborhood in which John S. Chase’s home resided. After reviewing the provided site plan of his cul-de-sac, one could not help but wonder if he was the last to purchase a lot there since the home was built so close to his neighbors (and none of the other homes on the street were as tightly spaced). What were the neighbors like and what did they think of the ever-evolving Chase home?

We highly recommend this book if you are interested in Texas history, civil rights, design and architecture. If you find yourself in this camp, then this will make an excellent coffee table book for your collection.