San Antonio-based artist, David Alcantar, was born in Laredo and went to Marshall High School in San Antonio. He attended the University of Texas, receiving his B.F.A. in 2000 and his M.F.A from the University of Colorado-Boulder in 2004.

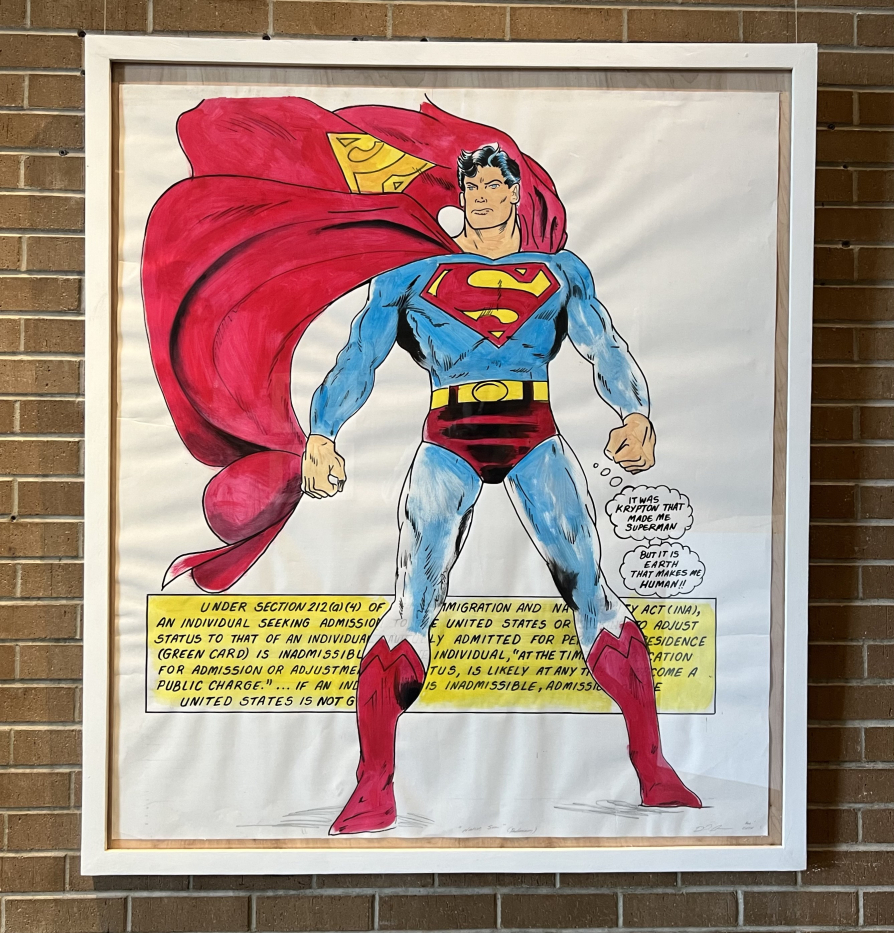

Since November 2016, Alcantar has been working on a project using the topic of heroism and the familiar iconography of Superman to conjure up questions about the origins of how and where we place our faith in humanity.

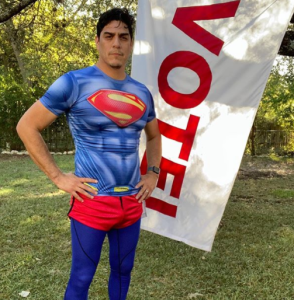

His most recent body of work, The Superman Project, includes paintings, 2D and 3D works, as well as performance art where he donned the regalia of Superman and ran an impressive length carrying a flag with one straightforward call to action, “VOTE”. His performance art, officially entitled "The American", included traveling to various locations during election time and running roughly the collective length of a marathon.

As a continuation of this series on heroism, he will be having an exhibition in Un Grito Gallery at Blue Star which opens on First Friday in December 2022, entitled “The Superman Project: Man of Steel, Man of Flesh, Man of Tomorrow, Person Today”.

As stated in a press release, “This exhibition is a partial culmination of his research about how societal negotiations surrounding power have defined American heroism, using the iconography of Superman as a tool to talk about those negotiations.”

We sat down with him to discuss his work and upcoming exhibition.

MiSA: What drives the message of your Superman Project for you? What have you observed?

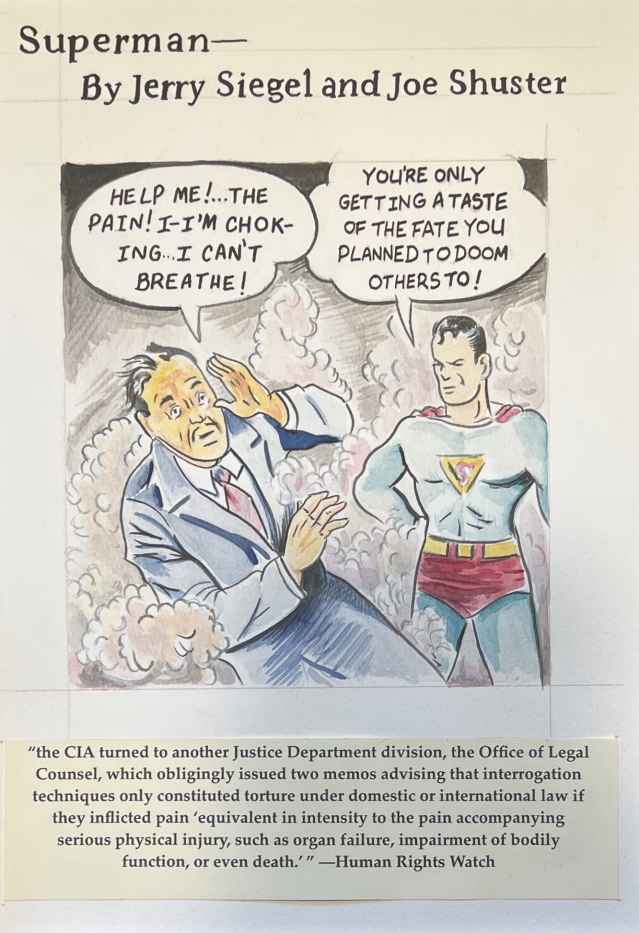

DA: The driving message of the Superman project is that the heroism and the salvation that we desire and for which we search doesn’t come from external sources, especially not from a single figure or source, but rather that it comes from ourselves and, more specifically, our faith in each other. Now, if you’re more inclined to a religious faith, like Christian theism, this may sound heretical, but even in that kind of Faith, the responsibility of action and belief is with you, the individual: you have to choose salvation and repentance. Heroism, and the salvation that is its byproduct, is never really any grand gesture, but instead is a “small”, practically invisible act of grace (undeserved favor and/or forgiveness). When we act towards another, for their benefit, even (and, perhaps, especially) when they don’t deserve it, we extend our faith in humanity and its ability to grasp the concept of “good” and expand its presence in the world. When we, instead, look to others (especially other humans, prone to mistake and fallibility) for rescue, we disempower ourselves and empower them. If enough people in a society do that, then you have a recipe for a bad actor to use that power corruptly, causing collateral damage to occur to people who were looking for salvation. And if such corruption and collateral damage happen then you adulterate the faith of people to believe in institutions and big concepts, like justice, governance, heroism, and humanity.

My assertion about grace, as the definitive characteristic of the hero, is not meant to be understood as a solution to all the problems that ail us as individuals or as a country or civilization, but hopefully, this exhibition is an effective reminder that civilization operates largely through our norms about goodness and morality, not laws. Norms are not inscribed in societies the way that laws are.

Laws are restrictive in a way that norms are not, and we all just experienced an administration that proved this with the way they were able to blatantly circumvent scrutiny because so much about the Presidency and government operates to a large degree by norms. One can act contrary to a norm because it’s not technically illegal to do so, but acting or doing “good” to avoid punishment is not the same as acting or doing good for the sake of “goodness”. There is no punishment that man could inflict on Superman were he to turn against earth and humanity. And despite all the capability and opportunity to seize power and things for himself, just because he can and no one can stop him, Superman remains steadfast in his faith in and his grace towards earth, humanity, and America. It may be fiction, but it’s admirable nonetheless.

MiSA: Tell us about your exhibition at Un Grito?

DA: The exhibition at Un Grito is a partial culmination of my years-long Superman project. Un Grito is a small artist-run space, so it would not have been able to accommodate all of the works I have made for this project. Therefore, I curated this exhibition to focus on one aspect of the Superman project, which is why the title for this show is “The Superman Project: Man of Flesh” (a play on Superman’s label as the Man of Steel). This exhibition focuses on the dilemma and myopia of “fantastical hero worship,” or hoping that someone else will fix things, rescue you, and keep you safe. There actually is no Superman. It’s just us, and how we choose (or not) to help one another.

MiSA: How do you define societal negotiations with regard to American heroism?

DA: A negotiation is a maneuvering between two or more parties/entities to come to an agreement about something. American heroism is tied to the mythology or American narrative that we subscribe to. We have to negotiate with ourselves, with our neighbors, with our elected officials what the narrative of this country is or should be. Depending on what the narrative/mythology is, determines who our heroes are. Right now, it seems like we are in a struggle with each other about the story of America and how it should be written. Figures that once were viewed as heroes are being toppled as their individual narratives are brought into clarity, but every American claims Superman as their champion. Even if he is not the first hero you think of, you claim him, because his story so remarkably overlaps with the story of America. His identity is so strong that when people across the globe see his image they simultaneously think of America.

MiSA: How has the Superman Project sparked conversation on the topic?

DA: In some cases, the conversations about particular Superman comic stories touch on the themes of authoritarianism, hero worship, and humanity that I am trying to investigate with the project. In other cases, it sparks conversation away from comics particularly to concepts of heroism and morality generally.

The Superman Runs (officially titled “The American”) sparks conversations about voting as an immediate power that people have, and that choosing not to exercise that power is giving it up to others. So it brings up conversations about civic participation as real-world heroism.

MiSA: Will the exhibition at Un Grito include a combination of your abstract works as well as the Superman subject matter?

DA: The exhibition at Un Grito is only showing pieces related to the Superman project. I like working with “bodies” of work. So I prefer to show those bodies of work separately so that the communication between the works is consistent and that the viewer can navigate between them seamlessly. Even though all of my work is about negotiation in some form or another, the forms that my work takes vary drastically from one “body” of work to another. The discussions about negotiation that my abstracted works make are dramatically different from the discussions that occur with and within the Superman project works.

MiSA: Do you feel that the Superman Project will continue after this exhibition? Do you have more in store for us?

DA: I originally hoped to have completed the Superman project in 2020, but then COVID happened and delayed my ability to work on it for two years. And while I had resolved to finish the project by this year, because the political landscape of this country remains so tumultuous and the yearning for salvation still so present in the society, I feel more pieces need to be made. It will just be that I will not narrow the focus of my manufacturing going forward on only Superman-related imagery. For example, beginning next year, I intend to return to a previous project that was not satisfactorily finished, referred to as the Tattoo Project.

MiSA: Is there anything else you would like to share regarding your work and the exhibition?

DA: The formal title for The Superman Project is “Man of Steel, Man of Flesh, Man of Tomorrow, Person Today”. Each subsection tackles a different aspect or facet of heroism and/or myth-making. The exhibition at Un Grito, for example, is “The Superman Project: Man of Flesh” and tackles the myopia of hero worship. “Man of Steel” would illustrate the real-world need for fantastical and aspirational heroes. So, the about 30 art pieces I currently have completed for this project are intended to be split between the subsections. My hope is to secure venues to exhibit each subsection of the project and then a venue that can show the entirety of the project at one time. We shall see.

The Superman Project was begun as a response to the election of Donald J. Trump as 45th president of the United States. When that happened, there was an immediate desire to try and understand how such an outcome occurred when all the conventional wisdom indicated the opposite. There was a societal and cultural negotiation that took place in order for this to occur and I wanted to investigate what the negotiation was. I was not alone in trying to solve this “mystery”; many think pieces were written in the aftermath about the election and the electorate.

As an artist, I wanted to tackle the issue from a visual perspective, but as is the challenge with depicting negotiation(s) in art, what would be the most effective image to use? In my initial research about the societal negotiation of Donald Trump as president, I was reminded of a thing that I heard a very successful local Marketing/Advertising/Design and Political strategist once say during a professional development session: “People make decisions emotionally more than they do rationally.” And in almost every piece I read about the election, there was a stated desire for someone to come and “Shake up” the political landscape, to “fix” a “broken” system, and the feeling that an outsider was just the person that would rescue us all. So, it became obvious, to me, then, to juxtapose Superman’s iconography, and our acceptance of him and his narrative as our American hero and champion, with our narrative and the narratives of our national “heroes”. But this feeling and this desire for heroism and salvation is not a recent political phenomenon. It recurs throughout American history, not because its uniquely American, but because it is uniquely human. Superman, on the other hand, is not human, and not even traditionally native to America, and yet, we claim him. He is ours. And we all desire, at least in some small part, to be just like him. That, to me, is worthy of visual investigation.

Exhibition: "The Superman Project: Man of Steel, Man of Flesh, Man of Tomorrow, Person Today”

Duration: Opens on Friday, December 2, 2022 from 7:00 pm - 10:00 pm. It can be viewed by appointment only until the closing reception on Thursday, December 15, 2022, from 7:00pm - 9:00pm.

Location: Un Grito Gallery (In the Upstairs Studios of the Blue Star Complex)

1420 South Alamo Street

San Antonio, TX 78204